While I began my baking prior to the start of the Pandemic, the pandemic has brought a lot of new bakers into the fold, all hoping to learn to make better bread, relieve stress, and have the wonderful aroma of fresh baking in their homes.

Many will have started with some variant of a “No Knead Artisan Bread” which is particularly easy, and if you have a good large-ish Dutch Oven, can make some amazing bread.

But you quickly go beyond that and want something … more.

Sourdough

I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, and one thing I have had access to most of my life was this amazing sourdough bread. It was tangy, chewy, and blissful, whether it was plain, or buttered, or made into a sandwich, or hollowed out to pour clam chowder into it, it was something memorable.

I realized when I moved to Arizona for a decade plus that while sourdough is available elsewhere, it wasn’t the same. That is because a sourdough is leavened with a natural yeast culture made from whatever yeasts are endemic in an area.

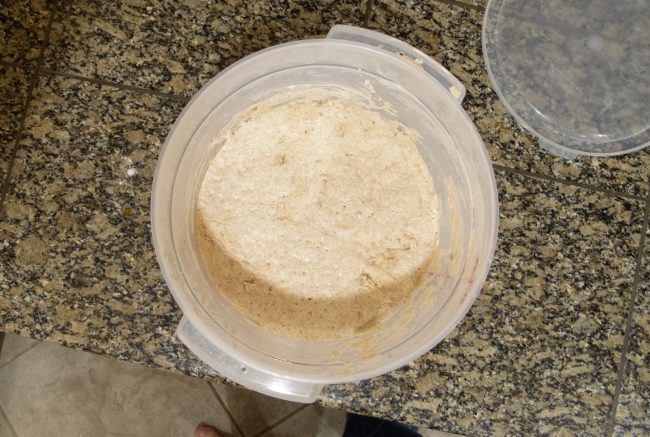

To make a starter, you literally just mix flour and water, and the traces of wild yeast that “fall” in while mixing become the culture.

You start it, but then with daily/weekly feedings you build up a strong culture, and it can become very active.

This natural yeast is a fickle beast. It isn’t a pure strain, like commercial packaged baking yeast, but instead is a culture that reflects the region and area it is “grown” in.

There is this aura of mystique. It is rumored that the starter at the major San Francisco bread bakeries has been in use since at least the Gold Rush days.

Prior to the availability of commercial yeast, all yeast leavened baked goods were made with sourdough starter. It was standard practice to reserve a little of the dough, and then to keep feeding it, and letting it mature and grow in the kitchen, as part of the daily tasks.

The Myths

It is not surprising that there is a mythos around naturally leavened bread. And a lot of misperceptions…

It’s hard

Some of these misperceptions are purposely spread by the guild members who want to protect their franchise. That is bad. But some are propagated by people who try to educate people. Yes, sourdough bread baking isn’t easy, and has a bit more effort – at least at the start – than commercial yeast leavened breads, but this leads to them using crutches to ostensibly lower the learning curve, and help novices get better results.

The King Arthur Flour recipe for budding sourdough crafters is their Rustic Sourdough, and it has your starter, and a little helper from commercial yeast. This helps the new to ensure that they get a good “lift” when baking. But, I found that it lead to over-proofing, and a taste that had more of the overtones of the commercial yeast than the sourdough starter. (The reason to hedge at first is that many novices want to bake before their starter is fully developed and predictable.)

But once you get a poofy, very active bubbling starter, you should be headed to the straight up, naturally leavened recipes. My go-to is the King Arthur Flour Extra Tangy Sourdough. It is a pretty simple recipe, it responds well to hand mixing (although you can use the dough hook if you have a Kitchen Aid stand mixer), and it is forgiving enough to hide a few of your goofs. Although, I can assure you that if you omit the salt, it will be a lousy loaf of bread.

Truth is, once you have a good starter going, and are keeping it fed and active, baking sourdoughs is not difficult.

The starter is too delicate

When you start your starter, you begin with flour (typically two types to start, wheat flour and something like rye or pumpernickel) and water. Over the course of a week of daily feedings, you finally see signs of life, and another week of daily feedings you get a very active starter.

You are proud of this. You spent 2 weeks (more or less) and a couple of bags of flour to get there. Naturally, like a parent, you want to be protective of your creation.

If you forget to feed it, you beat yourself up. Or, if you neglect it in the refrigerator, you think it might be ruined.

My advice to you is “Relax”. The reality is that the yeasts you plucked out of the environment to begin the creation of your starter are remarkably resilient. They are programmed to convert sugars into alcohols, and in the process to give off carbon dioxide. The alcohols are what provide that tang, and the carbon dioxide is what causes the dough to rise while proofing and baking.

Unless you are baking every day, you will not want to leave your starter out in your kitchen all the time (in the pioneer days, there wasn’t refrigeration, and you baked a lot of bread, so your starter was at ready access all the time).

So, you will store it in the refrigerator. After baking with it, you do a feeding cycle and then pop it on a shelf in the ‘fridge. It’s OK, we all do it.

The colder temperature reduces the fermentation rate, and ideally you should remove it, and feed it once a week to keep it healthy.

But what happens if you forget a few weeks? Have you ruined your starter?

No.

Just pull it out of the refrigerator, and feed it, keeping it in your kitchen. Like when you first made your starter, feed it every day, and in a couple of days, you will be back to its glory.

Note: when bacteria infect your starter, they will begin to convert some of the by products of fermentation into food and their waste products. There will likely be a black-ish discharge, and if you taste it, it will no longer be tangy, but will be off. However, this is rare, and in fact I have never experienced it. Even after leaving my starter in the fridge for 6 or more weeks between feeding.

My bread doesn’t rise quickly

Natural yeasts are less active than the commercial yeasts. Commercial yeasts are used by commercial bakers because they give predictable results, and because they generate a LOT of lift and rising action. If you are baking with commercial yeast, a complete bulk fermentation/forming/proofing process can be as little as three hours in a warm kitchen.

However, most sourdough recipes take 12-ish hours in the first bulk fermentation rise, then 6 – 8 hours for the second proof before baking. The temptation for new bakers is to rush the process, and that leads to dense, tight patterned crumb (the open gas spaces visible when you slice the bread). It will taste good, but it will not be a visually appealing loaf.

Sourdough takes a lot of work. Scratch that. It isn’t more work, but it is more patience. But it is worth it.

Do I have to throw away the bulk of my starter when feeding it?

The initiation of your starter will feel wasteful, but once you settle into a groove, you won’t be tossing so much out. But, even if you are using the refrigerator to retard the fermentation, you will have some cast off each week.

Fortunately, the kind folks at King Arthur Flour have all kinds of recipes that you can use your discarded starter for. Like making pancakes, or crumb coffee cake, or sourdough biscuits, or, well check out their link.

All great ideas, and while I don’t feel compelled to use all my starter discards to bake delish things (mainly because I don’t want to get to 300 pounds), if you have a family, you will find ample things to use your feeding discards for.

And the benefit? You will get more familiar with baking. Win – win!

Summary

For the novice, sourdough may seem like a long reach, but if you are patient, and attentive, you can make some fabulous bread that you can be proud of.

For the bulk of human history, the practice of cultivating and curating your local wild yeasts via a starter was the only way to have a yeast leavened loaf of bread.

Now you can too!